Welcome note

Welcome to the report of the Design Council / HEFCE fact finding visit to the US. As part of the process to develop and implement recommendations from the 'Cox Review of Creativity in Business' in the UK, a group of academics, officials and policy makers visited universities and design firms in California, Chicago and Boston. We were looking at multidisciplinary centres and courses that combine management, technology and design in order to develop creative and innovative graduates and businesses. Insights and information from the visit will inform proposals that UK universities and regional bodies are developing in response to the Cox review.

Friday, September 29, 2006

Tuesday, September 26, 2006

Thoughts on how visit informed Cox. By Ken Newton

Closer Links should be established between Universities and SMEs

Money seems high on the agenda with companies looking to get new insights and associated IPR from the universities. They also look to employ the best graduates and value them sufficiently to increment their salaries heavily. They get better response from universities and their students through high value competitions. Companies effectively sponsor universities so will want to ensure that links are strong to protect their investment. The ways in which students can get experience of a company and its practices seem better developed in terms of internships and co-operatives.

Higher education courses should better prepare students to work with and understand other specialists

There is obviously a strong emphasis on team working and the idea of T shaped people who are better prepared to work in teams. This appears to happen primarily at postgraduate level but a wider analysis would be helpful. The taking of two degrees, simultaneously, in two different disciplines seemed common, rather than degrees that were major / minor. In terms of students getting input from different areas in a structured way, particularly with reference to creative (design in this case) courses was not obvious but closer inspection of curricula may clarify. Most programs that we saw had a class that involved students from different academic backgrounds working as a team. Organising timetables was cited as a problem even for only one class. D School on the other hand is populated by people from different disciplines who are in fact chosen to come on the course, in part, by their background.

A common criterion was that graduates should be able to understand the language of other disciplines so as to be able to understand connections at a planning meeting or similar.

Centres of excellence should be established for multidisciplinary courses combining management studies, engineering and technology and the creative arts

I suppose the best example of this we saw was at North Western in Chicago. The structure allowed the coverage of 23 subjects over two years, with classes geared to the students needs – Turbo Finance was an example of a 5 week class covering the area. They used part time staff to deliver certain elements of the course who themselves had experience of multidisciplinary work through their other work. One wonders how much the creative aspects impact on the other areas, if at all, and whether the program is mainly for potential business leaders who just want a grasp of all areas of New Product Development.

Money seems high on the agenda with companies looking to get new insights and associated IPR from the universities. They also look to employ the best graduates and value them sufficiently to increment their salaries heavily. They get better response from universities and their students through high value competitions. Companies effectively sponsor universities so will want to ensure that links are strong to protect their investment. The ways in which students can get experience of a company and its practices seem better developed in terms of internships and co-operatives.

Higher education courses should better prepare students to work with and understand other specialists

There is obviously a strong emphasis on team working and the idea of T shaped people who are better prepared to work in teams. This appears to happen primarily at postgraduate level but a wider analysis would be helpful. The taking of two degrees, simultaneously, in two different disciplines seemed common, rather than degrees that were major / minor. In terms of students getting input from different areas in a structured way, particularly with reference to creative (design in this case) courses was not obvious but closer inspection of curricula may clarify. Most programs that we saw had a class that involved students from different academic backgrounds working as a team. Organising timetables was cited as a problem even for only one class. D School on the other hand is populated by people from different disciplines who are in fact chosen to come on the course, in part, by their background.

A common criterion was that graduates should be able to understand the language of other disciplines so as to be able to understand connections at a planning meeting or similar.

Centres of excellence should be established for multidisciplinary courses combining management studies, engineering and technology and the creative arts

I suppose the best example of this we saw was at North Western in Chicago. The structure allowed the coverage of 23 subjects over two years, with classes geared to the students needs – Turbo Finance was an example of a 5 week class covering the area. They used part time staff to deliver certain elements of the course who themselves had experience of multidisciplinary work through their other work. One wonders how much the creative aspects impact on the other areas, if at all, and whether the program is mainly for potential business leaders who just want a grasp of all areas of New Product Development.

Friday, September 22, 2006

Summary Report by Professor Penny Sparke, Pro Vice-Chancellor (Arts), Kingston University

Monday September 11th, 9.00 – 13.30

Hasso Plattner Institute of Design, Stanford University, Palo Alto

Meetings with George Kembel, Executive Director of Stanford d-School and Larry Leifer, Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Director, Center for Design Research

The d-School has been at least 20 years in the making. Its current aim is to produce ‘leaders’; to teach ‘out of the lecture theatre’; and to use ‘design thinking’ to inspire multi-disciplinary teams to solve problems in ways which do not necessarily result in new products or services but which might produce ‘business plans’, ‘implementation plans’, or ‘strategic plans’, among other things. The emphasis is upon the combination of business issues (viability), technical issues (feasibility), and human issues/values (usability).

The School’s ‘napkin manifesto’ includes the following aims:

• To create the best design school in the US

• To prepare future ‘innovators’, defined as ‘breakthrough thinkers and doers’ (The emphasis on people, rather than on abstract notions of ‘innovation’, provided a theme for the visit)

• To use ‘design thinking’

• To foster radical collaborations

• To tackle big projects

The d-School is not technically a school (but rather an ‘institute’) as it does not have its own students but takes them from a range of existing Stanford masters programmes (this was perceived by several people we spoke to later as a problem). Students are awarded a ‘medal of honour’.

The emphasis is on the creation of multi-disciplinary teams working on projects and on ensuring that thinking is balanced by doing. Discourse/dialogue is only half the equation and important questions, it is believed, arise through ‘doing’. Kembel emphasised the ‘process’ and stressed that all the d-School projects – some of which were ‘invented’ by members of Faculty (although they has to be ‘real world’ in nature – Larry Leifer commented that ‘the topic didn’t matter as it was the process that was important) and others of which were brought to them by industry – had to be ‘process conscious’. Some projects were ‘altruistic’ in nature, e.g., ‘handling emergency aftermaths’. It was emphasised, however, that projects had to be constrained.

The d-School’s primary asset is its students. Kembel explained how industrial collaborators soon came to understand this and that they gradually replaced their black suits with jeans and joined in with the University community.

Faculty staff were seen as ‘collaborators with students’ rather than as ‘sages on stages’. Kembel explained that staff members are subjected to critiques from other staff and students in this process.

Teams are surrounded by both staff and ‘coaches’ – the latter were characterised as ‘veteran design thinkers with teaching/industrial experience’.

The multi-disciplinary teams consist of people with expertise in the areas of business, engineering, design and social science – (the latter importantly includes ethnographers who were mentioned by many other people during the visit, as well as psychologists and artists). (It is important to note also that the d-School was conceived and initiated by product designers). In such a multi-disciplinary team people are not as hierarchically-oriented as they would be in a team of ‘like-minded’ people, Kembel explained. The focus is on the way in which the members of the team make decisions together and the process that underpins that. Team members have to quickly become ‘experts’ in fields outside their own.

The emphasis is upon the use of ‘design thinking’ as a common language to bring together people who speak different languages. The concept of ‘T’ shaped people (vertical = specialist, analytical depth/horizontal = breadth/empathy with other disciplines) is seen as crucial in this context. (This was mentioned at other visits, especially at IDEO).

The optimum size of a team was deemed to be 3 or 4. (this was emphatically reiterated at other visits) (Larry Leifer described 3 as ‘optimum’; 4 as ‘okay’; and 5 as ‘death’).

The class sizes at d-School were 24-30 and they came for around 10 weeks and undertook a number of projects (4/5) during that time.

The process the teams follow begins with quick initial research (including observation of users) followed by prototyping (up to 10 per project). This might involve using a workshop, making a video or doing spread sheets. Kembel described this as a ‘common sense’ process. Leifer re-emphasised that much learning takes place in the prototyping process and that it is the learning rather than the prototype that is important. Like Kembel he stressed that there is no method in the d-School approach to creativity and innovation and that prototyping ‘forces decision-making without reference to quantitative data’. Both stressed the importance of intuition. Each student has to keep a ‘design log’ and there is a ‘wiki website’ on which to record the process. There are no team leaders and the emphasis is on ‘what’s important for the process?’ and ‘how do you select ideas for projects?’. The students have to decide what is important. The main question is ‘what is the problem?’

The space, or ‘habitat’ in which innovation can occur is an important theme for the d-School (as it is for many of the places we visited) as it is seen as ‘governing how people behave’. D. School is working iteratively on a space planning exercise for a building it will occupy in 2009, funded by a $35 million gift by Hasso Plattner. It is housed in temporary space at present. (Leifer added that it is important that the space is ‘not precious or finished’ and that the team members have to be empowered to own and change the space and to have 24/7 access to it). Couches (sofas became a leitmotif on the visit!), coffee tables, large tables, common areas, flexible spaces (walls on wheels) and break out spaces are important. Personal space is limited (These themes were reiterated frequently during the visit). A loft/warehouse is seen as the ideal sort of space.

The difficult question of assessing student teamwork was discussed but not satisfactorily resolved.

Larry Leifer reiterated many of the points made by Kembel adding that his area of expertise is in cognitive science and that he has a group of PhD students who work individually and who ‘study people who study design’ in an ‘observatory’ context. His specialism is teamwork and he uses the notion of Jungian personality types. He is keen on maximum diversity in creative teams and the need for continual ‘unlearning’. He asked why designers don’t consciously ‘steal’ or ‘cite’ other people’s ideas as they do in other disciplines. He discussed the importance of IP in this context and explained that Stanford works mostly with large-scale, global companies (BMW, Daimler, Chrysler, Panasonic and Schick were mentioned) rather than SMEs as the latter don’t feel they have the time to engage in this sort of activity. (The word ‘immersive’ was used frequently here as elsewhere). Companies pay $75k to work with Stanford.

15.00 – 17.00

IDEO, 100 Forest Avenue, Palo Alto

Meeting with Tim Brown, CEO

David Kelley, the founder of IDEO, studied product design at Stanford 26 years ago (a student of Larry Leifer) and IDEO was a ‘spin-out’. Now IDEO thinking is coming back into the d-School.

IDEO is not an ‘industrial design’ company, but rather a ‘design thinking’ company which can tackle a much wider set of problems, although its core is in conventional design. (60% strategic projects/40% design projects). However objects are still seen as important ways of communicating strategies.

IDEO work with companies which desire growth (This was the case with all the design companies we visited). It also works with start-ups.

IDEO’s staff work across around 50 disciplines, focusing around business, technical issues and social science. Its emphasis is on ‘humanising technology’ and it works on service and space relationships (e.g., retail) and urban planning). The constant is ‘human-centred design’ and a ‘holistic’ way of doing things. They continue to ‘chase the interesting problems’. Their work covers the toy industry to medical products. One of their emphases is ‘story-telling’ and to this end they involve film-makers and writers.

IDEO’s starting point is that ‘designers have always had to understand a bit of everything’, therefore ‘design thinking’ is itself a multi-disciplinary process. Empathy for other disciplines is important. User observation is important. People with ‘hooks out to other disciplines’ are crucial in this context, but they must also have ‘knowledge of their core subject’. Tim Brown mentioned that this approach is being developed at Rhode Island School of Design, in Toronto, at Art Center (Pasadena) and at Berkeley.

Brown stressed the importance of ‘figuring out the right problem’ which might not have been the one the client came with. They need to question the brief.

IDEO’s aim is to develop long term relationships with clients. They work with some companies (e.g. Pepsi) which have no in-house designers and others (e.g., Proctor and Gamble) which have lots. It is difficult for them to work with SMEs as they may not have the capital to do something with the solution that IDEO has given them. However they see an eco-system of companies developing with ideas coming from small companies and large companies developing them (the model of small companies selling ideas to GOOGLE and YAHOO was mentioned). They work mostly with global companies. Brown fears that under-investment in British design education might mean that we loose the edge in this area (he is an RCA graduate). Like d-School they stressed that their ‘design thinking’ process was not a methodology. Brainstorming and prototyping are important as is use observation at the outset of a project. Brown talked about a ‘pick’n’mix’ approach and explained that you ‘cannot fix the process because it stifles innovation’. (This was re-iterated many times during the visit). Projects are rigorously managed.

IDEO has a matrix structure which means that all designers work across a range of projects.

There is lots of collaborative space and little personal space. They use a huge warehouse with project rooms down the sides and large collaborative spaces in the middle – large tables etc. A team might live in a project room for 3 months. They bring research material back to them. Lots of Post’it notes were being used (One of the visit’s most dominant themes!).

18.00

Dinner meeting with Jonathan Ive, Vice-President of Industrial Design, Apple Computers, hotel in San Francicso

This meeting was very different from the last two inasmuch as Ive, a highly creative and innovative designer, works in a ‘conventional’ way with a small, specialised, product design team. Unusually, however, he is on the board of Apple and clearly plays a key role within the company. This is undoubtedly due to the far-sightedness of the company’s CEO, Steve Jobs, who returned to the company in 1997 to launch the I-Mac and the I-Pod. The lesson of Apple, where the Cox Review is concerned, is that, as well as educating excellent designers, such as Ive, HE needs to educate industry ‘leaders’ who have an acute understanding of design, its process, and its economic and cultural benefits.

Ive gave us an account of his work experience at Apple. 90% of his time is spent designing. He is adamant that ‘it is a mistake to push designers to become business-people’ and he doesn’t consider himself one but he knows ‘how to make a product’. Having said that, he stated that, ‘you have to be a collection of people to make a product.’ He stressed that Apple’s goal was not to make money but to make the best products. It is, as he reminded us, the only company which deals with both software and hardware. He has Europeans in his design team and, like Brown, is worried that the UK is under-investing in design education. (He was educated at Northumbria University). His view of designers is that they should be ‘fanatical craftspeople’. He emphasised the unique character of Apple, explaining, for example, that it has no corporate guidelines book.

Tuesday September 12th, 12.00 – 14.00

Jump Associates LLC, San Mateo, California

Meeting with Alonzo Canada,

Jump operates rather like IDEO but it is a younger, much smaller (9 years old with 45 people as against 500) company. They specialise in design and innovation and aim to ‘reinvigorate products and services’ and help firms to meet their strategic objectives. They are a multi-disciplinary, highly collaborative practice (including ethnography and organisational psychology as they value social research) which, like IDEO, works with ‘clients who want to grow’. They bring together design (what’s possible, including technology?), business (what’s viable?) with culture (what’s desirable?). Jump’s teams include designers, engineers and marketing people but each individual is multi-disciplinary.

They employ people who have expertise in 2 of these areas and are open to learning about the third) (rather more demanding than d-School and IDEO who look for expertise in one area only. They can only use graduates or people with life/work experience. An ideal employee, for example, would be an anthropologist whose parents are designers!) They call these people their ‘resident schizophrenics’ and say that in the end they have to train their own people.

Examples of projects included, what will come after the SUV? How can a bank re-engage with is customers? How can e-bay express its identity? They try to approach problems in new ways and to look at the world from the consumer’s perspective.

The space in which they work is very important to them. They have created a stairwell at the heart of their building to facilitate chance encounters, conversations and exchanges of ideas. Public and café space is important as is what they call ‘neighbourhood spaces’, which are open plan spaces where people on different projects work closely together, and project rooms (one has cushions on the floor). They talk about ‘fostering random interactions and are interested in ideas ‘just coming up’. If they gain legs they follow them through even if there isn’t a client. Another project room has a gap at the top of the walls to avoid being in total isolation. They see spaces combining both fixed and fluid elements. People move between teams which are made up of 3-5 people. 6 is seen as too many. Post’it notes are everywhere! They don’t know what they are going to end up with when they start out on a project.

Jump, like IDEO, does abstract projects but communicates the solutions visually and concretely (a strong theme of the visit). It finds its ideas in Business journals (e.g. from work emanating from the Harvard Business School and ‘entertainment magazines.’ They have a magpie approach to both academic and popular ideas accessed through the media and put them side by side. They believe in different cultures of innovation – invent/execute/explore/apply - but are most keen to apply ideas rather than just to articulate them. They describe themselves as ‘intellectually curious’. Like IDEO they talk about ‘constructing narratives’ and they involve both narrative and linguistic analysis. Like many other people on the visit they quoted Starbucks as an innovation of significance in terms of the way it has provided a new space for teenagers – not a bar, not a school, not home - and it defines its customers in a new way. They do not attempt to define innovation but, like others, see it, in broad terms, as ‘invention with socio-economic impact’.

Wednesday September 13th, 9.00 – 10.30

Institute of Design, Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago

Meeting with Patrick Whitney, Director, and V. J. Kumar

The Institute of Design has developed a masters/PhD programme (120 masters students and 10 PhDs) which is design-led but which is directed at the business context. It takes a multi-disciplinary approach bringing together marketing people, engineers and designers. Whitney does not like the term ‘design thinking’ but nonetheless talks about the relevance of the ‘way designers think’ to solving business problems. In particular he isolates analytic thinking, prototyping and the importance of the retention of ambiguity and multiple options up to the end of the project. He says that this is ‘like the core action of the design process’ and claims that it is ‘more relevant to the way people are living’. He sees the application of this approach to the creation of products, services and organisations. He argues that this is the next evolutionary stage for design which started out as an ‘arts and crafts’ concept and he uses the term ‘design planning’.

The approach is based on the British-based Design Methods movement of the 1960s but it has been stretched to become more flexible in order to meet the needs of a new socio-economic and cultural context.

The staff of the I of D are involved with ‘executive level’ short courses focusing on ‘real life’ industry projects and development for designers (e.g., GK Design)

Their bottom line is the belief that ‘designers need a more formalised education’ and that they should no longer be seen as ‘exotics’. (Whitney saw the d-School as a ‘new name for an old product’). His definition of innovation was ‘top line growth’ or ‘new things that are adopted by customers.’(Ethnography was mentioned again, as was the idea of doing user observation exercises with disposable cameras)

V.J. Kumar presented what he describes as an ‘innovation tool kit’ which attempts to formalise Whitney’s approach diagrammatically. He defines innovation as ‘a new idea that is made viable in the market and adds value to users and providers’. He stressed that the design and innovation process ‘is not linear’.

11.00 – 12.30

Stuart Graduate School of Business, IIT, Chicago

Meeting with Zia Hassan, Dean Emeritus and Professor and Harvey Kahalas, Dean

For 4-5 years the School has run a joint/dual programme with the I of D which ends up with the award of two degrees – MBA/Masters in Design. It was stimulated by design students wanting to take business courses and aims to produce CEOs who will lead across design/business with Steve Jobs as the role model. The question was asked as to whether ‘design is a subset of the business discipline’.

There is no strong sense here that real multi-disciplinarity is occurring even though all the usual buzz words are being used. It seemed as the real aim is to inject a level of creativity into business education and practice, and create a niche MBA (there was much discussion about vanilla MBAs) and that the I of D is conveniently situated to provide that. Artists, poets and other ‘pure creatives’ could just as well be introduced if this is the real aim. There did not seem to be any understanding of ‘design thinking’ in a sophisticated way. It was also pointed out that IIT may be offering 2 courses which are in competition with each other rather than really developing synergies across disciplines.

13.30 – 16.00

Meetings with Craig Vogel, Director of Centre for Design Research and Innovation, University of Cincinatti, and Tom Fisher, Dean, College of Design, and Marc Swackhamer, Assistant Professor, Dept. of Architecture, University of Minnesota

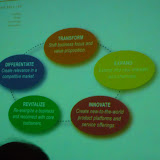

Craig Vogel presented his work at Cincinatti and outlined the new developments in US design education which are recognising the inherent multi-disciplinarity of design and the need to align it with new areas and use its ‘thinking’ to solve a broader range of problems. He talked about some of the problems of multi-disciplinarity, explaining, for example, that ‘business people and engineers are very uncomfortable if their goals are not clear’. He stressed the important role of human factors, cognitive psychology and ethnography. Apple and Starbucks were cited once again as leading innovators. He made an important point that ‘innovation is not driven by technology but by value’ and stated that the MFA/MDA are the new MBA.

The staff members from the University of Minnesota described their plans for a new, innovatory, product design course. /

17.00

Herbst LaZarBell, Chicago

Meeting with Walter Herbst and Mark Dziersk, Senior Vice President, Design

This is a fairly conventional design consultancy in the sense that it is very product-oriented but it uses much social research (including ethnographers) and multi-disciplinary teams in which individuals are learning from each other during the design process. Like the other companies visited it also works on strategy for its clients, especially in relation to brand languages. It roots its work in the consumer experience, which it sees as primarily emotional in nature, and observational research. The brand solution follows from this. It depends upon brainstorming and cross-functional groups and is interested in product innovation which results in radically newly-conceived products. The idea that nobody wants a drill, they want a hole, was voiced, and the example of a baby’s nail clipper with a magnifying glass in it, which results in fewer injured babies and less fingernail biting, was given.

The firm has a developed notion of the market which is less about market segmentation and more about ‘tribes’ and the fact that one person can belong simultaneously to many. ‘The brand comes from the product not the other way round’ it was explained and it was claimed that ‘good design is not good enough any more’.

Ive’s reluctance to let designers become businesspeople was reinforced by the idea expressed here that ‘ watching a designer give business advice is link watching a cat bark.’

The difficulty of finding ‘cross-over’ people was discussed ((cf. Jump). The anthropologists they employ, for example, ‘have to have an empathy for creativity’.

Teams of 3 – social scientist, designer, engineer – were favoured.

Some designers were trained in interview techniques. Sometimes the anthropologists act as pseudo-clients (they disappear at the engineering stage). Products are created in mock-up spaces, e.g., an iron in a laundry room.

Thursday September 14th, 9.00 – 11.00

Northwestern University, Evanston, Ill.

Meeting with Walter Herbst, Director, Master of Product Development Programme, School of Engineering and Applied Science

Herbst made a presentation about the Masters of Product Development course at Northwestern which is taught jointly with the Kellogg School of Management. The average age of students on the course is 37 and they attend for one day a week for 2 years. Most are sponsored by their employers. The curriculum aims to balance and blend ‘right and left’ brain activities and the course is team and project based. It aims to develop managers and includes ‘analysis of products and why they were designed the way they were.’ The course has more ‘doing’ in it than its Chicago Business School equivalent and integrates design and business more effectively.

11.30 – 13.30

Ford Engineering Center, Northwestern University

Meeting with Wally Hopp, Joint Masters Programme Director

There is also a ‘Master of Management and Manufacturing Design’ course at Northwestern which is based on an MBA but which includes an engineering programme in it ‘to give it depth’. The aim of the course is to produce team managers. The MBA element is taught at an accelerated rate. The course was developed in response to the US loss of global leadership in manufacturing in the early 1990s. (cf. masters courses in Engineering Management at MIT) Both products and services are embraced and ‘real life’ projects are undertaken (example of body-bags for use after a disaster was discussed). The example of Starbucks was given again.

An executive version of the course also exists.

Friday September 15th, 7.30 – 9.00

Group Meeting, Hotel@MIT

A number of emerging themes from the visit were identified at this point, listed in no particular order. They included:

• spaces for innovation

• dealing with ambiguity

• the conflation of innovation, creativity and design

• ‘design’ being applied to wide range of problems, not just product-oriented ones

• ‘design thinking’

• The importance of multi-disciplinary teams

• Business-led innovation masters courses/design-led innovation masters courses

• The danger of over-formalised design methods

• The need for ‘concreteness’

• The appeal of design in its breadth across the production/consumption cycle

• Design’s self-defining, integral role within manufacturing and business

• The role of design in the next industrial revolution

• The creation of business leaders

• The extension of products to services

• The absence of conversations with clients

• User-focused research (ethnography)

• Design’s essential multi-disciplinarity

10.00 – 12.00

Engineering Systems Division, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Mass

Meeting with Professor Joel Moses and Daniel Whitney

A presentation was given on a set of masters courses undertaken with the Sloan School of Management at MIT which bring together engineering, management and social science. They aim to produce ‘tomorrow’s leaders’ for manufacturing. They are project based and sometimes lead to real product development (a plastic paint can and a playground set were cited). The student team sizes are 6-7. The word ‘immersion’ was used again. As there is not a product design course at MIT links have been made with the Rhode Island School of Design. They were described as contributing ‘shape, colour and texture’ and as being able to ‘get the awkwardness out of products’. The SDM course is a distance learning course.

We were told that ‘most other business schools don’t want to mix with grubby engineers’ and that the collaboration didn’t work at Stanford.

The reason behind the lack of success of MIT’s link with Cambridge UK was given as the fact that it was a top-down process (directed by Gordon Brown) which was not rooted in a genuine, long-term association. MIT is more hopeful about a planned Portugal collaboration

12.00 – 15.00

MediaLab/DesignLab, MIT

Meeting with Bill Mitchell, Professor of Architecture and Media Arts and Sciences

Mitchell provided an overview of MediaLab’s background. It was formed 20 years ago and aims to provide ‘synthetic work across disciplines.’ Rooted in technological research it takes on projects which are linked to areas such as software and consumer electronics but it also works on concept cars, robotics, prosthetics etc. Work takes place on the ‘atelier’ model and it is based on activity rather than theory. Prototyping plays a very important role. It is multi-disciplinary and project-based. Teams are put together as required. The model of activity is research/theory/concrete realisation and the teams include engineers, artists, architects, computer scientists, physicists and many others. Mitchell mentioned including a brain scientist in a recent project. Currently there is a shift towards the life sciences – bio-technology in particular. Pharmaceutical science and geography are also included. BM says they shift to ‘where the intellectual action is.’ MediaLab also aims to focus on work which has social significance.

BM explained that, like Silicon Valley, Cambridge has a very lively industrial eco-system which keeps re-inventing itself.

Mitchell described the recent emergence of DesignLab which is only 6 months old. It is based on the MediaLab model but is more design- and ‘situation-specific’ and has a different approach to IP. A new building for DesignLab, designed by Fumiko Maki, is planned for 2009.

MediaLab’s teams are led by academic staff but made up of graduate students from across MIT as well as research assistants. Each project is funded externally and staff and students are paid for the duration of the project. Students gain credits. A few UG students are also involved. A job description is put out and applications are made.

The space in which MediaLab people work is very important to them (a recurrent theme). Its current building (an I.M.Pei design) is an open, black box performance space with a mezzanine floor built into it with personal/projects spaces on it. It has no external windows.

MediaLab is constantly in search of industrial funding and functions on the basis of an industrial consortium which brings in about $35 million annually. The companies involved have non-exclusive access to MediaLab’s work and ideas. Mitchell describes MediaLab’s work as ‘mostly upstream’. It is primarily concerned with ‘things that think’, ‘artefacts with intelligence’. Its aim is to ‘make digitally intelligent objects tangible’. It has a huge range of industrial sponsors, from automobile to telecommunications companies. It also initiates its own projects, e.g., Mitch Resnick’s toy work. Mitchell is involved with a ‘smart cities’ project.

Mitchell explained why MediaLab Europe, based in Dublin, was unsuccessful. The reasons were primarily financial.

MediaLab is ideas driven and offers visions of the future. It develops close intellectual relationships with its partners through events. It brings all its companies together once a year. Their main benefit is access to a stream of talented students. The Lab is currently working on a concept car for GM. It is a lightweight, electric, rentable car which stacks like supermarket trolleys and folds like luggage. ML is also working on a bus system for Paris, a motor-scooter for Piaggio and the creation of a 21st century village for Zambana in Italy.

Many of ML’s PhD students develop ‘spin-off’ companies.

Mitchell explained that MediaLab’s privileged relationship with corporations made for a difficult relationship with the rest of MIT.

Projects begin with brainstorming and the group quickly starts generating solutions based on big questions such as, in relation to cars, ‘can we get rid of the engine?’ Solutions are then group critiqued and technical research begins. BM characterises the ML design process as ‘getting something out before you are sure of the solution so that it can stimulate responses’. ML is NOT immersed in user culture although some ethnographic work does take place. The question ‘what would users think?’ is addressed. BM described what they do as ‘quick and dirty social science.’

BM talked about the importance of informal meeting places where ideas happen. He mentioned the importance of the Wagon Wheel restaurant in Silicon Valley as one example.

BM described the need for ‘designers who can surf the waves of technological innovation’ and the importance of real personal relationships.

Hasso Plattner Institute of Design, Stanford University, Palo Alto

Meetings with George Kembel, Executive Director of Stanford d-School and Larry Leifer, Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Director, Center for Design Research

The d-School has been at least 20 years in the making. Its current aim is to produce ‘leaders’; to teach ‘out of the lecture theatre’; and to use ‘design thinking’ to inspire multi-disciplinary teams to solve problems in ways which do not necessarily result in new products or services but which might produce ‘business plans’, ‘implementation plans’, or ‘strategic plans’, among other things. The emphasis is upon the combination of business issues (viability), technical issues (feasibility), and human issues/values (usability).

The School’s ‘napkin manifesto’ includes the following aims:

• To create the best design school in the US

• To prepare future ‘innovators’, defined as ‘breakthrough thinkers and doers’ (The emphasis on people, rather than on abstract notions of ‘innovation’, provided a theme for the visit)

• To use ‘design thinking’

• To foster radical collaborations

• To tackle big projects

The d-School is not technically a school (but rather an ‘institute’) as it does not have its own students but takes them from a range of existing Stanford masters programmes (this was perceived by several people we spoke to later as a problem). Students are awarded a ‘medal of honour’.

The emphasis is on the creation of multi-disciplinary teams working on projects and on ensuring that thinking is balanced by doing. Discourse/dialogue is only half the equation and important questions, it is believed, arise through ‘doing’. Kembel emphasised the ‘process’ and stressed that all the d-School projects – some of which were ‘invented’ by members of Faculty (although they has to be ‘real world’ in nature – Larry Leifer commented that ‘the topic didn’t matter as it was the process that was important) and others of which were brought to them by industry – had to be ‘process conscious’. Some projects were ‘altruistic’ in nature, e.g., ‘handling emergency aftermaths’. It was emphasised, however, that projects had to be constrained.

The d-School’s primary asset is its students. Kembel explained how industrial collaborators soon came to understand this and that they gradually replaced their black suits with jeans and joined in with the University community.

Faculty staff were seen as ‘collaborators with students’ rather than as ‘sages on stages’. Kembel explained that staff members are subjected to critiques from other staff and students in this process.

Teams are surrounded by both staff and ‘coaches’ – the latter were characterised as ‘veteran design thinkers with teaching/industrial experience’.

The multi-disciplinary teams consist of people with expertise in the areas of business, engineering, design and social science – (the latter importantly includes ethnographers who were mentioned by many other people during the visit, as well as psychologists and artists). (It is important to note also that the d-School was conceived and initiated by product designers). In such a multi-disciplinary team people are not as hierarchically-oriented as they would be in a team of ‘like-minded’ people, Kembel explained. The focus is on the way in which the members of the team make decisions together and the process that underpins that. Team members have to quickly become ‘experts’ in fields outside their own.

The emphasis is upon the use of ‘design thinking’ as a common language to bring together people who speak different languages. The concept of ‘T’ shaped people (vertical = specialist, analytical depth/horizontal = breadth/empathy with other disciplines) is seen as crucial in this context. (This was mentioned at other visits, especially at IDEO).

The optimum size of a team was deemed to be 3 or 4. (this was emphatically reiterated at other visits) (Larry Leifer described 3 as ‘optimum’; 4 as ‘okay’; and 5 as ‘death’).

The class sizes at d-School were 24-30 and they came for around 10 weeks and undertook a number of projects (4/5) during that time.

The process the teams follow begins with quick initial research (including observation of users) followed by prototyping (up to 10 per project). This might involve using a workshop, making a video or doing spread sheets. Kembel described this as a ‘common sense’ process. Leifer re-emphasised that much learning takes place in the prototyping process and that it is the learning rather than the prototype that is important. Like Kembel he stressed that there is no method in the d-School approach to creativity and innovation and that prototyping ‘forces decision-making without reference to quantitative data’. Both stressed the importance of intuition. Each student has to keep a ‘design log’ and there is a ‘wiki website’ on which to record the process. There are no team leaders and the emphasis is on ‘what’s important for the process?’ and ‘how do you select ideas for projects?’. The students have to decide what is important. The main question is ‘what is the problem?’

The space, or ‘habitat’ in which innovation can occur is an important theme for the d-School (as it is for many of the places we visited) as it is seen as ‘governing how people behave’. D. School is working iteratively on a space planning exercise for a building it will occupy in 2009, funded by a $35 million gift by Hasso Plattner. It is housed in temporary space at present. (Leifer added that it is important that the space is ‘not precious or finished’ and that the team members have to be empowered to own and change the space and to have 24/7 access to it). Couches (sofas became a leitmotif on the visit!), coffee tables, large tables, common areas, flexible spaces (walls on wheels) and break out spaces are important. Personal space is limited (These themes were reiterated frequently during the visit). A loft/warehouse is seen as the ideal sort of space.

The difficult question of assessing student teamwork was discussed but not satisfactorily resolved.

Larry Leifer reiterated many of the points made by Kembel adding that his area of expertise is in cognitive science and that he has a group of PhD students who work individually and who ‘study people who study design’ in an ‘observatory’ context. His specialism is teamwork and he uses the notion of Jungian personality types. He is keen on maximum diversity in creative teams and the need for continual ‘unlearning’. He asked why designers don’t consciously ‘steal’ or ‘cite’ other people’s ideas as they do in other disciplines. He discussed the importance of IP in this context and explained that Stanford works mostly with large-scale, global companies (BMW, Daimler, Chrysler, Panasonic and Schick were mentioned) rather than SMEs as the latter don’t feel they have the time to engage in this sort of activity. (The word ‘immersive’ was used frequently here as elsewhere). Companies pay $75k to work with Stanford.

15.00 – 17.00

IDEO, 100 Forest Avenue, Palo Alto

Meeting with Tim Brown, CEO

David Kelley, the founder of IDEO, studied product design at Stanford 26 years ago (a student of Larry Leifer) and IDEO was a ‘spin-out’. Now IDEO thinking is coming back into the d-School.

IDEO is not an ‘industrial design’ company, but rather a ‘design thinking’ company which can tackle a much wider set of problems, although its core is in conventional design. (60% strategic projects/40% design projects). However objects are still seen as important ways of communicating strategies.

IDEO work with companies which desire growth (This was the case with all the design companies we visited). It also works with start-ups.

IDEO’s staff work across around 50 disciplines, focusing around business, technical issues and social science. Its emphasis is on ‘humanising technology’ and it works on service and space relationships (e.g., retail) and urban planning). The constant is ‘human-centred design’ and a ‘holistic’ way of doing things. They continue to ‘chase the interesting problems’. Their work covers the toy industry to medical products. One of their emphases is ‘story-telling’ and to this end they involve film-makers and writers.

IDEO’s starting point is that ‘designers have always had to understand a bit of everything’, therefore ‘design thinking’ is itself a multi-disciplinary process. Empathy for other disciplines is important. User observation is important. People with ‘hooks out to other disciplines’ are crucial in this context, but they must also have ‘knowledge of their core subject’. Tim Brown mentioned that this approach is being developed at Rhode Island School of Design, in Toronto, at Art Center (Pasadena) and at Berkeley.

Brown stressed the importance of ‘figuring out the right problem’ which might not have been the one the client came with. They need to question the brief.

IDEO’s aim is to develop long term relationships with clients. They work with some companies (e.g. Pepsi) which have no in-house designers and others (e.g., Proctor and Gamble) which have lots. It is difficult for them to work with SMEs as they may not have the capital to do something with the solution that IDEO has given them. However they see an eco-system of companies developing with ideas coming from small companies and large companies developing them (the model of small companies selling ideas to GOOGLE and YAHOO was mentioned). They work mostly with global companies. Brown fears that under-investment in British design education might mean that we loose the edge in this area (he is an RCA graduate). Like d-School they stressed that their ‘design thinking’ process was not a methodology. Brainstorming and prototyping are important as is use observation at the outset of a project. Brown talked about a ‘pick’n’mix’ approach and explained that you ‘cannot fix the process because it stifles innovation’. (This was re-iterated many times during the visit). Projects are rigorously managed.

IDEO has a matrix structure which means that all designers work across a range of projects.

There is lots of collaborative space and little personal space. They use a huge warehouse with project rooms down the sides and large collaborative spaces in the middle – large tables etc. A team might live in a project room for 3 months. They bring research material back to them. Lots of Post’it notes were being used (One of the visit’s most dominant themes!).

18.00

Dinner meeting with Jonathan Ive, Vice-President of Industrial Design, Apple Computers, hotel in San Francicso

This meeting was very different from the last two inasmuch as Ive, a highly creative and innovative designer, works in a ‘conventional’ way with a small, specialised, product design team. Unusually, however, he is on the board of Apple and clearly plays a key role within the company. This is undoubtedly due to the far-sightedness of the company’s CEO, Steve Jobs, who returned to the company in 1997 to launch the I-Mac and the I-Pod. The lesson of Apple, where the Cox Review is concerned, is that, as well as educating excellent designers, such as Ive, HE needs to educate industry ‘leaders’ who have an acute understanding of design, its process, and its economic and cultural benefits.

Ive gave us an account of his work experience at Apple. 90% of his time is spent designing. He is adamant that ‘it is a mistake to push designers to become business-people’ and he doesn’t consider himself one but he knows ‘how to make a product’. Having said that, he stated that, ‘you have to be a collection of people to make a product.’ He stressed that Apple’s goal was not to make money but to make the best products. It is, as he reminded us, the only company which deals with both software and hardware. He has Europeans in his design team and, like Brown, is worried that the UK is under-investing in design education. (He was educated at Northumbria University). His view of designers is that they should be ‘fanatical craftspeople’. He emphasised the unique character of Apple, explaining, for example, that it has no corporate guidelines book.

Tuesday September 12th, 12.00 – 14.00

Jump Associates LLC, San Mateo, California

Meeting with Alonzo Canada,

Jump operates rather like IDEO but it is a younger, much smaller (9 years old with 45 people as against 500) company. They specialise in design and innovation and aim to ‘reinvigorate products and services’ and help firms to meet their strategic objectives. They are a multi-disciplinary, highly collaborative practice (including ethnography and organisational psychology as they value social research) which, like IDEO, works with ‘clients who want to grow’. They bring together design (what’s possible, including technology?), business (what’s viable?) with culture (what’s desirable?). Jump’s teams include designers, engineers and marketing people but each individual is multi-disciplinary.

They employ people who have expertise in 2 of these areas and are open to learning about the third) (rather more demanding than d-School and IDEO who look for expertise in one area only. They can only use graduates or people with life/work experience. An ideal employee, for example, would be an anthropologist whose parents are designers!) They call these people their ‘resident schizophrenics’ and say that in the end they have to train their own people.

Examples of projects included, what will come after the SUV? How can a bank re-engage with is customers? How can e-bay express its identity? They try to approach problems in new ways and to look at the world from the consumer’s perspective.

The space in which they work is very important to them. They have created a stairwell at the heart of their building to facilitate chance encounters, conversations and exchanges of ideas. Public and café space is important as is what they call ‘neighbourhood spaces’, which are open plan spaces where people on different projects work closely together, and project rooms (one has cushions on the floor). They talk about ‘fostering random interactions and are interested in ideas ‘just coming up’. If they gain legs they follow them through even if there isn’t a client. Another project room has a gap at the top of the walls to avoid being in total isolation. They see spaces combining both fixed and fluid elements. People move between teams which are made up of 3-5 people. 6 is seen as too many. Post’it notes are everywhere! They don’t know what they are going to end up with when they start out on a project.

Jump, like IDEO, does abstract projects but communicates the solutions visually and concretely (a strong theme of the visit). It finds its ideas in Business journals (e.g. from work emanating from the Harvard Business School and ‘entertainment magazines.’ They have a magpie approach to both academic and popular ideas accessed through the media and put them side by side. They believe in different cultures of innovation – invent/execute/explore/apply - but are most keen to apply ideas rather than just to articulate them. They describe themselves as ‘intellectually curious’. Like IDEO they talk about ‘constructing narratives’ and they involve both narrative and linguistic analysis. Like many other people on the visit they quoted Starbucks as an innovation of significance in terms of the way it has provided a new space for teenagers – not a bar, not a school, not home - and it defines its customers in a new way. They do not attempt to define innovation but, like others, see it, in broad terms, as ‘invention with socio-economic impact’.

Wednesday September 13th, 9.00 – 10.30

Institute of Design, Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago

Meeting with Patrick Whitney, Director, and V. J. Kumar

The Institute of Design has developed a masters/PhD programme (120 masters students and 10 PhDs) which is design-led but which is directed at the business context. It takes a multi-disciplinary approach bringing together marketing people, engineers and designers. Whitney does not like the term ‘design thinking’ but nonetheless talks about the relevance of the ‘way designers think’ to solving business problems. In particular he isolates analytic thinking, prototyping and the importance of the retention of ambiguity and multiple options up to the end of the project. He says that this is ‘like the core action of the design process’ and claims that it is ‘more relevant to the way people are living’. He sees the application of this approach to the creation of products, services and organisations. He argues that this is the next evolutionary stage for design which started out as an ‘arts and crafts’ concept and he uses the term ‘design planning’.

The approach is based on the British-based Design Methods movement of the 1960s but it has been stretched to become more flexible in order to meet the needs of a new socio-economic and cultural context.

The staff of the I of D are involved with ‘executive level’ short courses focusing on ‘real life’ industry projects and development for designers (e.g., GK Design)

Their bottom line is the belief that ‘designers need a more formalised education’ and that they should no longer be seen as ‘exotics’. (Whitney saw the d-School as a ‘new name for an old product’). His definition of innovation was ‘top line growth’ or ‘new things that are adopted by customers.’(Ethnography was mentioned again, as was the idea of doing user observation exercises with disposable cameras)

V.J. Kumar presented what he describes as an ‘innovation tool kit’ which attempts to formalise Whitney’s approach diagrammatically. He defines innovation as ‘a new idea that is made viable in the market and adds value to users and providers’. He stressed that the design and innovation process ‘is not linear’.

11.00 – 12.30

Stuart Graduate School of Business, IIT, Chicago

Meeting with Zia Hassan, Dean Emeritus and Professor and Harvey Kahalas, Dean

For 4-5 years the School has run a joint/dual programme with the I of D which ends up with the award of two degrees – MBA/Masters in Design. It was stimulated by design students wanting to take business courses and aims to produce CEOs who will lead across design/business with Steve Jobs as the role model. The question was asked as to whether ‘design is a subset of the business discipline’.

There is no strong sense here that real multi-disciplinarity is occurring even though all the usual buzz words are being used. It seemed as the real aim is to inject a level of creativity into business education and practice, and create a niche MBA (there was much discussion about vanilla MBAs) and that the I of D is conveniently situated to provide that. Artists, poets and other ‘pure creatives’ could just as well be introduced if this is the real aim. There did not seem to be any understanding of ‘design thinking’ in a sophisticated way. It was also pointed out that IIT may be offering 2 courses which are in competition with each other rather than really developing synergies across disciplines.

13.30 – 16.00

Meetings with Craig Vogel, Director of Centre for Design Research and Innovation, University of Cincinatti, and Tom Fisher, Dean, College of Design, and Marc Swackhamer, Assistant Professor, Dept. of Architecture, University of Minnesota

Craig Vogel presented his work at Cincinatti and outlined the new developments in US design education which are recognising the inherent multi-disciplinarity of design and the need to align it with new areas and use its ‘thinking’ to solve a broader range of problems. He talked about some of the problems of multi-disciplinarity, explaining, for example, that ‘business people and engineers are very uncomfortable if their goals are not clear’. He stressed the important role of human factors, cognitive psychology and ethnography. Apple and Starbucks were cited once again as leading innovators. He made an important point that ‘innovation is not driven by technology but by value’ and stated that the MFA/MDA are the new MBA.

The staff members from the University of Minnesota described their plans for a new, innovatory, product design course. /

17.00

Herbst LaZarBell, Chicago

Meeting with Walter Herbst and Mark Dziersk, Senior Vice President, Design

This is a fairly conventional design consultancy in the sense that it is very product-oriented but it uses much social research (including ethnographers) and multi-disciplinary teams in which individuals are learning from each other during the design process. Like the other companies visited it also works on strategy for its clients, especially in relation to brand languages. It roots its work in the consumer experience, which it sees as primarily emotional in nature, and observational research. The brand solution follows from this. It depends upon brainstorming and cross-functional groups and is interested in product innovation which results in radically newly-conceived products. The idea that nobody wants a drill, they want a hole, was voiced, and the example of a baby’s nail clipper with a magnifying glass in it, which results in fewer injured babies and less fingernail biting, was given.

The firm has a developed notion of the market which is less about market segmentation and more about ‘tribes’ and the fact that one person can belong simultaneously to many. ‘The brand comes from the product not the other way round’ it was explained and it was claimed that ‘good design is not good enough any more’.

Ive’s reluctance to let designers become businesspeople was reinforced by the idea expressed here that ‘ watching a designer give business advice is link watching a cat bark.’

The difficulty of finding ‘cross-over’ people was discussed ((cf. Jump). The anthropologists they employ, for example, ‘have to have an empathy for creativity’.

Teams of 3 – social scientist, designer, engineer – were favoured.

Some designers were trained in interview techniques. Sometimes the anthropologists act as pseudo-clients (they disappear at the engineering stage). Products are created in mock-up spaces, e.g., an iron in a laundry room.

Thursday September 14th, 9.00 – 11.00

Northwestern University, Evanston, Ill.

Meeting with Walter Herbst, Director, Master of Product Development Programme, School of Engineering and Applied Science

Herbst made a presentation about the Masters of Product Development course at Northwestern which is taught jointly with the Kellogg School of Management. The average age of students on the course is 37 and they attend for one day a week for 2 years. Most are sponsored by their employers. The curriculum aims to balance and blend ‘right and left’ brain activities and the course is team and project based. It aims to develop managers and includes ‘analysis of products and why they were designed the way they were.’ The course has more ‘doing’ in it than its Chicago Business School equivalent and integrates design and business more effectively.

11.30 – 13.30

Ford Engineering Center, Northwestern University

Meeting with Wally Hopp, Joint Masters Programme Director

There is also a ‘Master of Management and Manufacturing Design’ course at Northwestern which is based on an MBA but which includes an engineering programme in it ‘to give it depth’. The aim of the course is to produce team managers. The MBA element is taught at an accelerated rate. The course was developed in response to the US loss of global leadership in manufacturing in the early 1990s. (cf. masters courses in Engineering Management at MIT) Both products and services are embraced and ‘real life’ projects are undertaken (example of body-bags for use after a disaster was discussed). The example of Starbucks was given again.

An executive version of the course also exists.

Friday September 15th, 7.30 – 9.00

Group Meeting, Hotel@MIT

A number of emerging themes from the visit were identified at this point, listed in no particular order. They included:

• spaces for innovation

• dealing with ambiguity

• the conflation of innovation, creativity and design

• ‘design’ being applied to wide range of problems, not just product-oriented ones

• ‘design thinking’

• The importance of multi-disciplinary teams

• Business-led innovation masters courses/design-led innovation masters courses

• The danger of over-formalised design methods

• The need for ‘concreteness’

• The appeal of design in its breadth across the production/consumption cycle

• Design’s self-defining, integral role within manufacturing and business

• The role of design in the next industrial revolution

• The creation of business leaders

• The extension of products to services

• The absence of conversations with clients

• User-focused research (ethnography)

• Design’s essential multi-disciplinarity

10.00 – 12.00

Engineering Systems Division, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Mass

Meeting with Professor Joel Moses and Daniel Whitney

A presentation was given on a set of masters courses undertaken with the Sloan School of Management at MIT which bring together engineering, management and social science. They aim to produce ‘tomorrow’s leaders’ for manufacturing. They are project based and sometimes lead to real product development (a plastic paint can and a playground set were cited). The student team sizes are 6-7. The word ‘immersion’ was used again. As there is not a product design course at MIT links have been made with the Rhode Island School of Design. They were described as contributing ‘shape, colour and texture’ and as being able to ‘get the awkwardness out of products’. The SDM course is a distance learning course.

We were told that ‘most other business schools don’t want to mix with grubby engineers’ and that the collaboration didn’t work at Stanford.

The reason behind the lack of success of MIT’s link with Cambridge UK was given as the fact that it was a top-down process (directed by Gordon Brown) which was not rooted in a genuine, long-term association. MIT is more hopeful about a planned Portugal collaboration

12.00 – 15.00

MediaLab/DesignLab, MIT

Meeting with Bill Mitchell, Professor of Architecture and Media Arts and Sciences

Mitchell provided an overview of MediaLab’s background. It was formed 20 years ago and aims to provide ‘synthetic work across disciplines.’ Rooted in technological research it takes on projects which are linked to areas such as software and consumer electronics but it also works on concept cars, robotics, prosthetics etc. Work takes place on the ‘atelier’ model and it is based on activity rather than theory. Prototyping plays a very important role. It is multi-disciplinary and project-based. Teams are put together as required. The model of activity is research/theory/concrete realisation and the teams include engineers, artists, architects, computer scientists, physicists and many others. Mitchell mentioned including a brain scientist in a recent project. Currently there is a shift towards the life sciences – bio-technology in particular. Pharmaceutical science and geography are also included. BM says they shift to ‘where the intellectual action is.’ MediaLab also aims to focus on work which has social significance.

BM explained that, like Silicon Valley, Cambridge has a very lively industrial eco-system which keeps re-inventing itself.

Mitchell described the recent emergence of DesignLab which is only 6 months old. It is based on the MediaLab model but is more design- and ‘situation-specific’ and has a different approach to IP. A new building for DesignLab, designed by Fumiko Maki, is planned for 2009.

MediaLab’s teams are led by academic staff but made up of graduate students from across MIT as well as research assistants. Each project is funded externally and staff and students are paid for the duration of the project. Students gain credits. A few UG students are also involved. A job description is put out and applications are made.

The space in which MediaLab people work is very important to them (a recurrent theme). Its current building (an I.M.Pei design) is an open, black box performance space with a mezzanine floor built into it with personal/projects spaces on it. It has no external windows.

MediaLab is constantly in search of industrial funding and functions on the basis of an industrial consortium which brings in about $35 million annually. The companies involved have non-exclusive access to MediaLab’s work and ideas. Mitchell describes MediaLab’s work as ‘mostly upstream’. It is primarily concerned with ‘things that think’, ‘artefacts with intelligence’. Its aim is to ‘make digitally intelligent objects tangible’. It has a huge range of industrial sponsors, from automobile to telecommunications companies. It also initiates its own projects, e.g., Mitch Resnick’s toy work. Mitchell is involved with a ‘smart cities’ project.

Mitchell explained why MediaLab Europe, based in Dublin, was unsuccessful. The reasons were primarily financial.

MediaLab is ideas driven and offers visions of the future. It develops close intellectual relationships with its partners through events. It brings all its companies together once a year. Their main benefit is access to a stream of talented students. The Lab is currently working on a concept car for GM. It is a lightweight, electric, rentable car which stacks like supermarket trolleys and folds like luggage. ML is also working on a bus system for Paris, a motor-scooter for Piaggio and the creation of a 21st century village for Zambana in Italy.

Many of ML’s PhD students develop ‘spin-off’ companies.

Mitchell explained that MediaLab’s privileged relationship with corporations made for a difficult relationship with the rest of MIT.

Projects begin with brainstorming and the group quickly starts generating solutions based on big questions such as, in relation to cars, ‘can we get rid of the engine?’ Solutions are then group critiqued and technical research begins. BM characterises the ML design process as ‘getting something out before you are sure of the solution so that it can stimulate responses’. ML is NOT immersed in user culture although some ethnographic work does take place. The question ‘what would users think?’ is addressed. BM described what they do as ‘quick and dirty social science.’

BM talked about the importance of informal meeting places where ideas happen. He mentioned the importance of the Wagon Wheel restaurant in Silicon Valley as one example.

BM described the need for ‘designers who can surf the waves of technological innovation’ and the importance of real personal relationships.

Thursday, September 21, 2006

Observations and thoughts – on the plane home. By James Moultrie

Regionality and design: danger of replication

There was a different perspective on design in each of the locations visited. This may well reflect the specific social, political and economic context of each area. At Stanford, the influence of silicon valley has driven an innovation model that is appropriate for rapidly changing mass produced consumer goods. The consultancies and design schools are formed around this context. In Chicago and Boston, the schools and consultancies have a stronger engineering emphasis, which is appropriate given the more mechanically focused industries in these regions. There is a danger therefore in replicating the different approaches, without carefully considering the needs of each region. In the UK, the optimum way of delivering design education and the content of each program might be very different in different regions.

Danger of superficiality

The emergence of easily understood ‘design methods’ raises a potential concern of superficiality. It is evident that with minimal training, senior business people can engage in ethnographic research and post-it driven brainstorming. This is an important breakthrough, in the same way as it is important for the Technical Director to be able to read a balance sheet. However, no sensible business person would assume that they could create the business accounts on their own, without professional help. The subjective nature of design methods perhaps provides a danger that the exec will become a poorly qualified ‘doer’ rather than using this new insight to bring in the real professionals. Thus design education for senior people must not trivialise design. It must instead encourage execs to understand the deep skills that the designers bring, so that their only response is to know that they should employ professionals.

The real value of methods and tools

The emerging collection of design tools, focused on user research, lo-fi prototyping, concept generation and communication play a key role in the design process. They are a design aid and may help the effectiveness or efficiency of the design process. Most importantly however, they enable the intangible elements of the design process to be better communicated to people in business. Thus, when concepts are presented, it no longer appears that they have appeared out of the ether, but as a result of serious consideration.

The design process is different to the ‘new product introduction process’

Companies must manage new product introduction and typically have a process to enable this, often based on some form of stage gate process. By necessity, this process is normally linear and mandates a sequence of decision points, often demanding reliable, qualitative and unambiguous information. The design process in contrast is highly iterative and typically demands the use of highly ambiguous data. The more radical the design, the more ambiguous this data. Designers are able to operate effectively in this ambiguous process. However, it is not easy to align this iterative and ambiguous process with a firm’s need for a linear and unambiguous one.

Design skill vs design thinking

Design thinking is not the same as design skill. Designers take many years to develop their skills in conceiving, creating and communicating a range of artefacts and experiences.

Good designers have always considered more than just the product

Many designers are artefact focused (product, furniture, building etc). This is their bread and butter and often their initial inspiration. However, designers have always considered more than just the product. Dreyfus was instrumental in the development of products as branded objects. Sinel (in the 1920s) wrote about ‘corporate identity’. Good designers instinctively consider their creations in the wider context in which they will be consumed and used. Good designers have also always considered the way in which the artefact may earn money for the organisation – they might just not have called it the business model.

Design is not at the centre, but an equal partner with marketing, engineering etc

There is a danger of thinking about design and designers as the holders of the holy grail. Designers play a key role and where their value isn’t recognised, then efforts need to be taken to raise awareness. However, this should also be true for other key business skills. Great design with poor marketing, poor supply chain management or weak product strategy is also a recipe for failure.

I shaped, T Shaped, Stool shaped

Undergraduate qualifications form the foundation of the ‘I’ in ‘I’ shaped people. At this stage the seeds of horizontal aspects of the T should be sown. Hence, the creation of the ‘engineer in society’ component of engineering degrees, as a requirement for chartership, addressing business and societal aspects of engineering. Marketing, accounting and engineering undergraduates should have an introduction to design. Similarly, design undergraduates should have an introduction to these other disciplines. Work experience develops the ‘T’. Further education later in life might extend the ‘T’ or potentially lengthen the ‘I’. Only in later career might someone be lucky enough to develop multiple legs and be called (slightly worryingly) ‘stool shaped’!

There was a different perspective on design in each of the locations visited. This may well reflect the specific social, political and economic context of each area. At Stanford, the influence of silicon valley has driven an innovation model that is appropriate for rapidly changing mass produced consumer goods. The consultancies and design schools are formed around this context. In Chicago and Boston, the schools and consultancies have a stronger engineering emphasis, which is appropriate given the more mechanically focused industries in these regions. There is a danger therefore in replicating the different approaches, without carefully considering the needs of each region. In the UK, the optimum way of delivering design education and the content of each program might be very different in different regions.

Danger of superficiality

The emergence of easily understood ‘design methods’ raises a potential concern of superficiality. It is evident that with minimal training, senior business people can engage in ethnographic research and post-it driven brainstorming. This is an important breakthrough, in the same way as it is important for the Technical Director to be able to read a balance sheet. However, no sensible business person would assume that they could create the business accounts on their own, without professional help. The subjective nature of design methods perhaps provides a danger that the exec will become a poorly qualified ‘doer’ rather than using this new insight to bring in the real professionals. Thus design education for senior people must not trivialise design. It must instead encourage execs to understand the deep skills that the designers bring, so that their only response is to know that they should employ professionals.

The real value of methods and tools

The emerging collection of design tools, focused on user research, lo-fi prototyping, concept generation and communication play a key role in the design process. They are a design aid and may help the effectiveness or efficiency of the design process. Most importantly however, they enable the intangible elements of the design process to be better communicated to people in business. Thus, when concepts are presented, it no longer appears that they have appeared out of the ether, but as a result of serious consideration.

The design process is different to the ‘new product introduction process’

Companies must manage new product introduction and typically have a process to enable this, often based on some form of stage gate process. By necessity, this process is normally linear and mandates a sequence of decision points, often demanding reliable, qualitative and unambiguous information. The design process in contrast is highly iterative and typically demands the use of highly ambiguous data. The more radical the design, the more ambiguous this data. Designers are able to operate effectively in this ambiguous process. However, it is not easy to align this iterative and ambiguous process with a firm’s need for a linear and unambiguous one.

Design skill vs design thinking

Design thinking is not the same as design skill. Designers take many years to develop their skills in conceiving, creating and communicating a range of artefacts and experiences.

Good designers have always considered more than just the product

Many designers are artefact focused (product, furniture, building etc). This is their bread and butter and often their initial inspiration. However, designers have always considered more than just the product. Dreyfus was instrumental in the development of products as branded objects. Sinel (in the 1920s) wrote about ‘corporate identity’. Good designers instinctively consider their creations in the wider context in which they will be consumed and used. Good designers have also always considered the way in which the artefact may earn money for the organisation – they might just not have called it the business model.

Design is not at the centre, but an equal partner with marketing, engineering etc

There is a danger of thinking about design and designers as the holders of the holy grail. Designers play a key role and where their value isn’t recognised, then efforts need to be taken to raise awareness. However, this should also be true for other key business skills. Great design with poor marketing, poor supply chain management or weak product strategy is also a recipe for failure.

I shaped, T Shaped, Stool shaped

Undergraduate qualifications form the foundation of the ‘I’ in ‘I’ shaped people. At this stage the seeds of horizontal aspects of the T should be sown. Hence, the creation of the ‘engineer in society’ component of engineering degrees, as a requirement for chartership, addressing business and societal aspects of engineering. Marketing, accounting and engineering undergraduates should have an introduction to design. Similarly, design undergraduates should have an introduction to these other disciplines. Work experience develops the ‘T’. Further education later in life might extend the ‘T’ or potentially lengthen the ‘I’. Only in later career might someone be lucky enough to develop multiple legs and be called (slightly worryingly) ‘stool shaped’!

What are designers for? By John Miller

Part of this agenda is supply driven - our design graduates are an undertapped resource. Our courses traditionally prepare them for the design industry, design practice or designer-making. A tiny amount of design graduates go for "graduate jobs" and neither are they well prepared to carve themselves out useful and fulfilling careers in SMEs.